Chau Er-dai (1917-1995), named Tonghe at birth, given name Zhongping, was born on Jan. 12, 1917, in Zhenjiang City in Jiangsu Province, China. The second eldest in his family, Chau was a soft-spoken child with a rather direct manner, earning him the nickname “Er-dai” (dim-witted second-born) — a name that he would later adopt for himself. Chau lived until 79 years old. When he was a child, his parents paid for him to be home-schooled in traditional Chinese literature, including the “four books,” the five Confucian classics and the Northern Song chronicle Zizhi Tongjian (A Mirror for the Wise Ruler). He threw himself into the study of poetry and verse like a contemporary literati, and would later graduate from the Politics Department of Northwest University in Xi'an. Between 1944 and 1946 he served as county commissioner for Sanyuan, Jiangle and Linsen counties in Fujian Province, but after arriving in Taiwan in 1949, lived in seclusion in Taichung's Taiping Township. In 1952 he took up a position as a senior administrative officer for the Taiwan Provincial Government, and 12 years later was promoted to general manager of the Agricultural and Industrial Development Co. It was in this year that his name started attracting attention in Taiwan and overseas after one of his Chinese ink paintings was taken into the collection of the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, Italy. He retired early in 1969 to devote himself more fully to his art, which he exhibited around the world in the years between 1965 and 1993, including Italy, Spain, Australia, the Netherlands, France, Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong.

In 1985, he was invited by the Coordination Council for North American Affairs (now the Taiwan Council for US Affairs) to hold a touring solo exhibition of 70 US cities. Shortly thereafter in 1988, the Penghu County Government, as part of the “rural art galleries” program organized by the Council of Cultural Affairs (now the Ministry of Culture), offered him a residency in Penghu and a plot of land for him to design and build a residence and studio that he called Yinu Ju (“Slave to Art Residence”), later renamed Er-dai Gallery. During the time he lived there, he produced a wide range of works, including ink and Western-style paintings, calligraphy, sketches, seal carvings, statues, ceramics, prints, photographs and poetry. On his passing in 1995, his entire oeuvre of 1,500 works created there was donated to the Penghu County Government and the Er-dai Gallery, which holds an annual exhibition of his works. The Penghu County Government named the road in front of his gallery Tonghe Road after his birth name to honor the contributions Chau made to Penghu.

Chau had originally wanted to study art in Suzhou, but as he encountered resistance to the idea from his family, he never received any formal arts training. Regardless, he became a talented painter who did not limit himself to any specific technique or medium, nor was he constrained or influenced by any artistic tradition or trend. His works exhibited a unique style and individual character, earning him the moniker “amateur artist.”

For Chau, the most important thing in painting was to convey the spirit of the subject matter — if the painting had no inherent substance, then no matter how good the artist's tools, the painting would not be able to express the artist's intent. Because of his awareness of the impermanence of life and search for his inner self, his easygoing and open-minded nature is inadvertently revealed in the lines of his prose and poetry, even while his firm grounding in the classics is expressed through use of literary quotes. The artist's published works include Menghen (“Dream Traces”), Dai Hua Dai Hua (“Paintings and Writings of Chao Er-dai”), Er-dai Shuimo (“Chinese Ink Paintings by Chao Er-dai”), Shiyi Ge Er-dai (“Eleven Works by Chao Er-dai”) and Rensheng Xiaopin (“Life Sketches”).

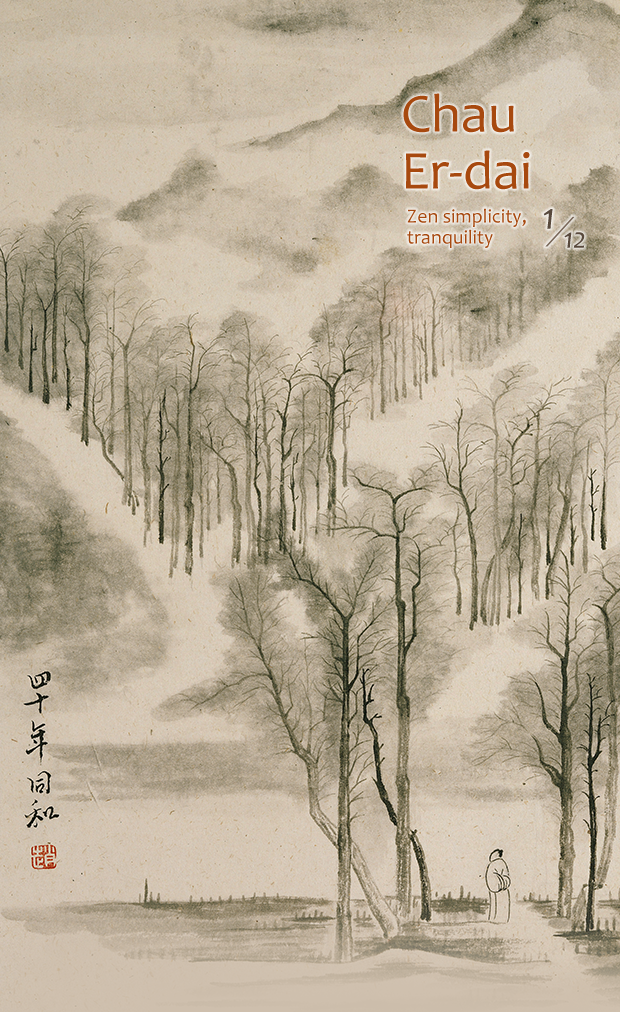

Chau Er-dai had a fascination with painting from a very early age, and as an adult devoted himself to traditional Chinese ink painting. From his studies of classical works, Western contemporary art and a range of other sources, he developed his own unique style characterized by images drafted from simple outlines. In 1973, on the invitation of the National Museum of History, he held the well-received Chau Er-dai Chinese Ink Painting exhibition, displaying 99 of his works in simple, economical brushwork.

In 1980 after having a dream that involved ceramics, Chau turned his hand to clay, making pieces as his fancy took him in a natural, organic process. Five years later, he was invited by the museum to participate in the first Ceramics Biennial, for which he displayed pieces that explored zen, simplicity, tranquility and solitude. Yet of all the many types of work he exhibited, it was his Chinese ink paintings and ceramics that attracted the most attention.

In 1996, to mark the first anniversary of Chau's passing, the National Museum of History held the Chau Er-dai Memorial Exhibition, offering an overview of his life's work and achievements with an accompanying exhibition catalog.

The museum has 114 of Chao Er-dai's variable works, 109 of which were generously donated by his family after the memorial exhibition.